Electricity

Dir. Elizabeth S Acevedo

An existential sci-fi short about the borders of sentience, the capacity for computers to love, and the idea of god to self aware beings.

IN THE STYLE OF TRANSCENDENTALISM & CINÉMA DU LOOK.

Director’s Statement:

On the Nature of Love and Robot

“I am an idealist. I am romantic, messy and emotional. I am fantastical in the way I interpret experience. However, this personal and innate approach to life is not ignorant of, nor incompatible with, my metatheory that we are all, rudimentarily speaking, robots.

Being matter, and so being members of the universal system of physics, we unequivocally adhere to physical law — most simply, cause and effect. Operant conditioning, the process by which our behaviors develop, illustrates our similarity to computerized systems. I may appreciate the beauty that blooms from our complicated natures, yet I still acknowledge that such beauty is merely a consequence of our deterministic subscription — a certain sheen atop a steel slab, which is not fixed but transient, a product of perspective. I even often pretend I am an active agent — that is, not a robot — because it makes the experience of living seemingly more ‘purposeful,’ a feature of life that logically, I renounce. In the Old Testament, God is said to have created Man in his image, but if that were so, Man would coexist under metaphysical law. Will is an illusion, though an easy interpretation of our operations, given that our ability to understand our operations is, at this time, limited…

“…In ELECTRICITY, Man created robot in his image. I imagine the robots worship humans, and humans worship nothing, save for the total, unobscured wonder of the universe.

The AI robots represent the nature of Man as I have described them, as any psychologist would — computerized beings, passive to their internal mechanisms. While the robots’ behavior is at the surface spontaneous, willful, motivated and personal, it only reflects their source code and all the code’s amendments made over time reacting to environmental consequences.

The humans, as viewed by the robots, represent the nature of Man as seen by the idealist/romantic — exceptional, free agents, wholly autonomous thinkers. Within the context of the film, humans have evolved to immeasurable physiological and intellectual lengths, such that their perspective has become divine. It can be assumed that their organic construction has developed impossibly to appear as though they function independently of physical law. They are gods — at least in the eyes of their dear robots.

Together, a human and its personal robot reflect the irreconcilable duality of how we can view ourselves — autonomous and nonautonomous.”

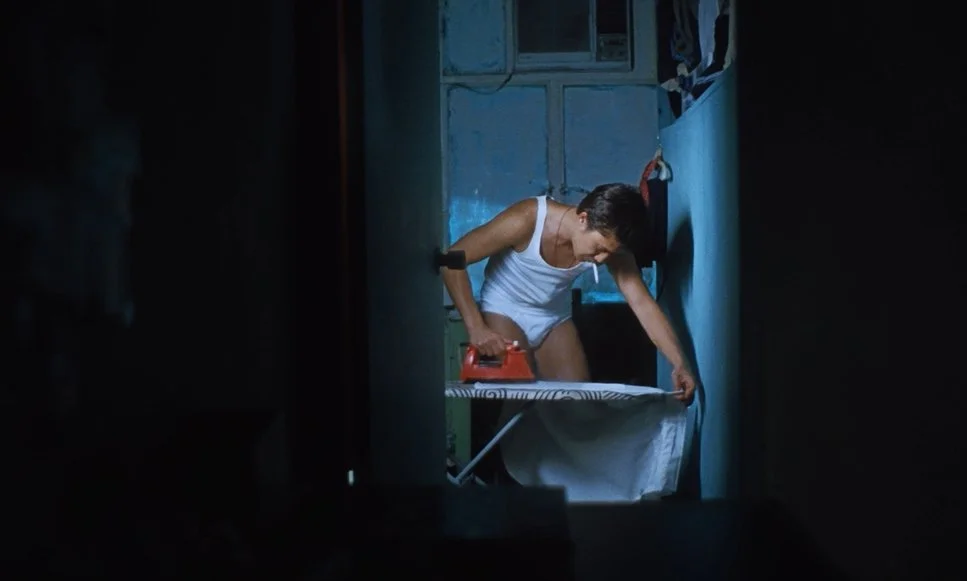

Love becomes the central topic within which this delineation of the nature of being is examined. Real emotion is void in the robots’ code, so the robots cannot love while the humans do. The robots can at most appear in behavior to love while observing voyeuristically and wishfully (‘wishful,’ I use in the most basic sense of being ‘motivated to obtain’) the true love that humans share.

Applying the psychoanalyst’s lens to protagonist Mica, a robot who refuses to accept her robot boyfriend’s apparent earnest affection, she can be metaphorically understood as any real person who — due to genetic predispositions and/or past experiences — has become disillusioned, guarded, distrustful or detached from romantic affairs. She sleeps with her boyfriend but refuses his prompts for emotional depth. Though a robot in this sci-fi, she is no different than any formerly heartbroken, avoidant character of reality.

Together, each of Mica’s scenic spheres — professional, social and romantic —paints a picture of my past year’s exploration of how people connect with themselves, others and the world around them.